El Salvador

Introduction

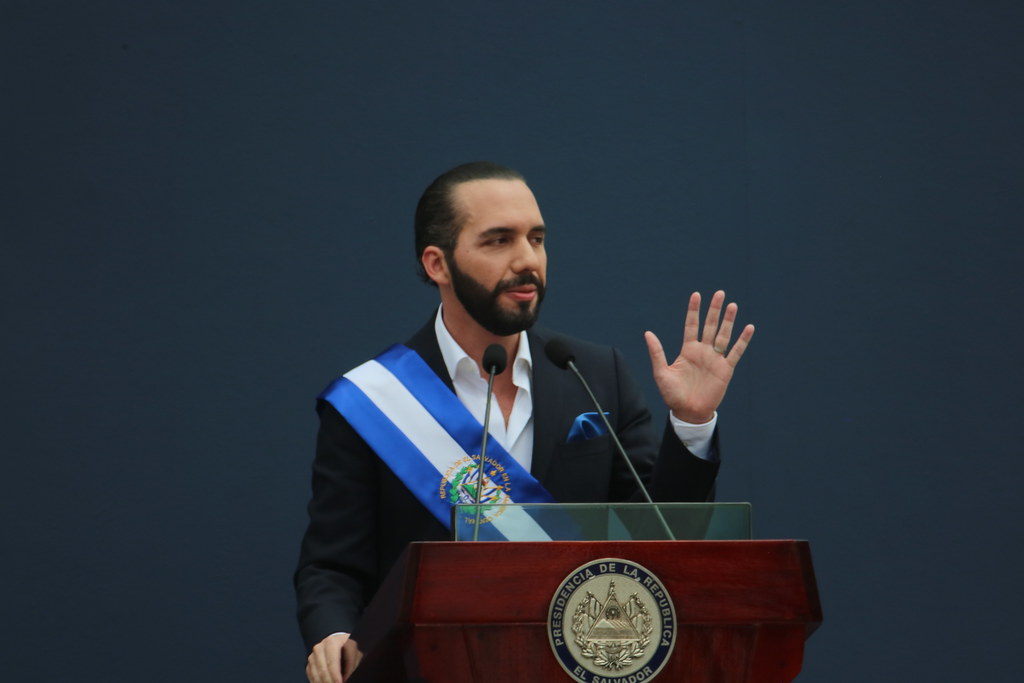

Since assuming the presidency on June 1, 2019, Nayib Bukele has tightened his grip on power at the expense of eroding democracy and rule of law. At the beginning of this year, the ruling party secured a majority in the Legislative Assembly allowing it to pass laws without negotiating with the opposition and to completely reshuffle the Constitutional Chamber whose rulings until then had stifled the government. The fruits of this for Bukele came fast, with the new handpicked judges wasting little time green-lighting his re-electoral ambitions albeit in express contravention to the country’s Constitution.

For now nothing seems to make a dent in the high popularity of the president who on his Twitter account describes himself as “the world’s coolest dictator”. Indeed this was a factor used to persuade the Chamber to approve Bukele’s potential re-election, the argument being that the controls on presidential turnover had their origins in containing presidents no longer popular with the people. That being said, recent weeks have witnessed as yet unseen social discontent that could presage changes in the public mood.

How did it get to this? Below, we analyze some of the key political-institutional developments over the last two years.

Security and regulation of the pandemic: strained relations between the three power branches

Nayib Bukele swept to power on June 1, 2019 with 53.1% of the vote, defeating the two main political forces for long alternating in power, namely ARENA and FMLN. However, this victory margin jarred with the composition of the legislature. And since the Legislative Assembly was only renewed this year, that meant Bukele had to coexist until then with a mostly government-hostile parliament.

Tensions soon frayed. Following Bukele’s accusations that lawmakers were willfully blocking his government’s agenda, on February 9, 2020 army personnel stormed the Assembly building amid extraordinary scenes, demanding the approval of a credit-line for the president’s crime-fighting initiative.

Controversy flared further following Covid-19, with the Assembly refusing to extend an emergency order to May 2020. Ignoring this, the executive decreed the extension unilaterally, placing restrictions on free movement and assembly. The Constitutional Chamber responded by declaring the move (and its related decrees) unconstitutional – which the government again ignored.

New Ideas becomes Assembly’s biggest party, judiciary gets steamrolled

The results of the legislative elections of February 2021 brought a new twist in the relationship between the Executive and the Assembly. With an electoral discourse criticizing the destabilizing forces of “old politics”, the President’s New Ideas party won by a landslide. In practice, this has meant that since May 1st this year, the ruling party has been the biggest Assembly party and, thanks to the support of its ally GANA, enjoys an effective overall majority.

Strengthened in parliament, it did not take long for it to embark on an erosion of institutional checks and balances. As soon as the new assembly members took office, they approved the dismissal of the judges of the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice and of the Attorney General, Raúl Melara.

The argument was that the magistrates had acted “against the Constitution, putting private interests above the health…of the entire population” – a reference to its rulings revoking the presidential decrees to extend the health emergency. The removal of the Attorney General was on the grounds of his alleged links to the opposition ARENA party which, it was contended, undermined his impartiality and independence.

None of this went unnoticed by the international community, prompting strong criticism raised from the OAS, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Vice President of the United States. Bukele retorted that “we are cleaning our house… and that is none of your business”.

Four other subsequent events have darkened thel picture further.

First, on June 4, 2021, the work of the International Commission against Impunity in El Salvador (CICIES in Spanish), created through an agreement with the OAS in September 2019, was abruptly brought to a halt.

Second, on August 31, the Assembly approved a new Judicial Career Law that automatically retires judges who are over 60, or have careers as judges exceeding 30 years. According to local media, this will affect more than 200 magistrates, equivalent to one third of the judges in the country.

Then, in the same session, a Law for the Reform of the Attorney General’s Office was approved, which foresees the possibility of the “temporary or permanent transfer of members of the prosecutorial career for justified reasons of convenience”. This has been interpreted as a means to effectively remove judiciary officials seen as hostile to the government. It is important to mention here that the former Attorney General, Raul Melara, before being dismissed, had been investigating multiple allegations of corruption in different ministries.

Finally, on September 21, the Legislative Assembly elected the new members of the National Council of the Judiciary (CNJ in Spanish), the institution in charge of selecting judges before the Supreme Court of Justice, who – in turn – elect the heads of the lower courts in the judicial pyramid.

Closing the circle: restrictions on access to public information

Since the middle of last year, multiple and systematic actions to undermine access to public information and the autonomy of the guarantor body, the Institute for Access to Public Information (IAIP in Spanish), have been taken.

In September 2020, Bukele modified by decree the regulations of the Law on Access to Public Information by increasing the discretionary powers of the president and appointed three like-minded commissioners who, months later, voted to no longer record the body’s sessions.

In addition, in April of this year Bukele ordered the dismissal of commissioner Liduvina Escobar, on the grounds of “probable undertaking of acts that affect the functioning of the Institute and non-compliance with her duties in office”. Escobar has not yet been removed, although she looks set to be after a request she filed to challenge her dismissal was ignored.

And then there was a bill presented last July 13 by the Ministry of the Interior which seeks to modify substantial aspects of the Law of Access to Public Information. Among them, it classifies the public sector wealth declarations as confidential, creates new mechanisms hindering access to information, and increases the powers of the president of the IAIP, who will be able to make decisions without the endorsement of the remaining commissioners. The reform has not yet been approved, but looks set to be very soon.

What awaits? Reelection, constitutional reform…and civil resistance?

Having amassed an unusual degree of power and with two years left of his mandate, Bukele would then, as we have seen, turn his attention to the Constitution which, in its article 154, expressly prohibits presidential reelection. That appears subject to interpretation, however, with the new Constitutional Chamber giving the go-ahead on September 3 this year for Bukele to seek a second presidential term in 2024. Contradicting previous jurisprudence, it ordered the Supreme Electoral Tribunal to enable the candidacy of “a person who holds the Presidency of the Republic and has not been President in the immediate previous period” (in this case 2014-2019) as long as the candidate for the new immediate period has taken a “leave of absence during the six months prior to the election”.

In parallel, the government is promoting a constitutional reform that includes the extension of the presidential term to 6 years and the reduction of the waiting term for reelection, thus ignoring Article 248 which establishes that articles referring to the alternation of the presidential exercise cannot be reformed. It should be noted that the draft also foresees the granting of constitutional rank to the IAIP and the Government Ethics Tribunal, the creation of a Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office and the replacement of the Constitutional Chamber by a Constitutional Tribunal.

But why seek the backing of the court if the government has the necessary parliamentary majority to approve the constitutional reform in the assembly? The answer is that, if Bukele did this, for the reform to take effect it would need to be ratified by the next Legislative Assembly, which can’t happen before 2024, and with the support of two thirds of deputies.

With the limits of democracy now stretched to breaking point, signs of a change to the public mood are beginning to surface. During the month of September there were several demonstrations – unprecedented until now – under the slogan “For democracy and the reestablishment of the rule of law”. Citizens protested against the abuses of power by the government, its removal of judges, the capture of the judiciary and the consolidation of power around a single political figure.

Yet the protesters were met with a president labelling them as criminals and terrorists, with particular anger levelled at a member of the executive committee of the Association of Journalists of El Salvador (APES in Spanish). On September 30, the capital woke up to its streets flooded with police. It remains to be seen if these nascent stirrings of dissent can be kept at bay by the government or rather continue or even escalate in the months to come.